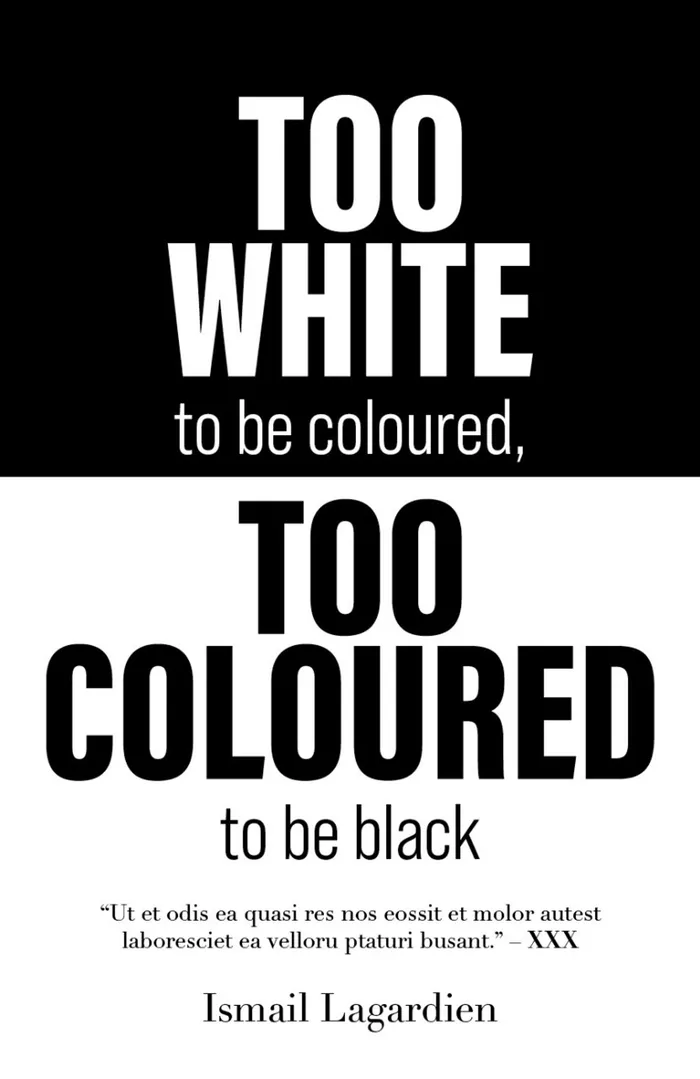

Book Extract: Too white to be coloured, too coloured to be black - on the search for home and meaning

Book cover. Supplied image.

A dazzling hybrid of memoir, commentary, first-hand observation and analysis, encapsulating defining moments of contemporary South African history and society. Largardien,s book forces a conversation between the present and the past of a country racked by racial injustice. In exposing details of his life he provides an indictment of South Africa's politics. Amid it all are his own struggles with being. He pauses on his own failures and shortcomings in search of freedom; looking back as if to find more pain in the past to fill the emptiness of displacement and meaninglessness.

Tortured by psychological and physical violence and struggles with his “coloured” white skin and green eyes, he drifts away from the ties that bind one and moves towards displacement.

Eventually Lagardien comes to accept his own helplessness and lack of purpose, without surrendering responsibility for his own choices. A triumphant marriage between intellectual rigour and personal disillusionment.

Extract

I am shuttered in my container home 600m as the crow flies from an exclusive beach which I have visited only two or three times in almost two years. I am recovering from spinal surgery I had barely a month ago, and maxillofacial and dental surgeries I have had since October. I am unable to do much more than sit and write for an hour or two at a time. The painkillers make me drowsy, and force me to lay down for hours at a time. I should probably explain.

It was a normal spring day. I was on my usual shopping drive along a country road from Kleinmond to Pringle Bay – a couple of coastal villages due east of Cape Town across False Bay and further east along the southern Atlantic as it breaks on the craggy shore.

The road from Pringle Bay to Kleinmond is non-descript. Unless you like the sight of boulders stacked one on top of the other, and that look like dog shit that’s baked in the sun for too long and is now a pale grey and hard. It’s a winding road along the slopes of the Overberg Mountains on the north with the South Atlantic breaking on a rocky coastline.

Kleinmond lies along a series of towns and villages – the most prominent of which is Hermanus, probably the second most important destination for wealthy white people (after Stellenbosch) as they make their way south in retirement, and into the arms of the Democratic Alliance, which represents their interests. Kleinmond and Pringle Bay, for that matter, is home mainly to retired old white folk, homes of absentee landlords who live upcountry or summer homes of Europeans. I am neither of that, and still not sure why I bought the plot of land and built a home here. There is something appealing about anonymity…

At the western end of the road and up the slopes above Kleinmond, in part, a legacy of spatial apartheid and in part, an informal settlement of (black) people who came to the area in search of work and a better life, is a reminder of the iniquities of South African society. It’s about a 2km walk from the shopping centre of Kleinmond to the informal settlement. Almost always after doing my shopping in Kleinmond and heading back home westward to Pringle Bay, 8-10km along the R44, I stop for some of the old ladies who walk along the road carrying refilled gas canisters or bags of groceries and who live in the informal settlement on the outskirts of town.

On that day in early October 2020, then eight months into the Covid-19 pandemic, I stopped along the road to offer a ride to “only two people, please,” begging them, “you must wear your face masks over your mouth and nose, please”. It was a simple routine I had gone through for a couple of years except for the face masks. This time, I invited two ladies onto the back seat. There’s usually at least five people who crowd into the car when I stop to give someone a ride. There is usually no public transport between many small towns in the country. I had shopping bags and a camera on the passenger seat and on the floor in front of the passenger seat. We drove along quietly. It’s usually a jovial affair. This time I looked repeatedly and fearfully in the rearview mirror to make sure that nobody’s mask had slipped. I turned the air conditioner up higher, and opened the front windows.

Approaching the “non-white” part on the north bank of the R44 from Kleinmond one of the ladies said: “You can drop us here, meneer. Dankie.” They got out and we waved goodbye. “Stay safe and healthy. Siyabulela,” is said. As soon as they were out of the car I maniacally sprayed the inside of the car with alcohol-based sanitiser, opened all windows… sound of the Guardian Football weekly podcast and set off for home.

A few metres ahead there were tyres stacked across the road with a few large boulders blocking passage. I snailed along, curiously. I had heard that the ring leader of an abalone smuggler had been caught, and that people in the informal settlement were up in arms.

BANG!

A rock thrown by a protester struck my halfway-opened driver-side window. The window was shattered. If it had been closed the rock would not have gotten into the car.

The inside of the car was aglitter with pieces of glass. In the rearview mirror I saw blood on my glasses. I moved the mirror, and saw that the rock had split my lip in two places and ripped several teeth from my mouth. I panicked. Protesters often set cars alight, along with drivers.

The rock broke my jaw and left the insides of my mouth in a bloody mess; it was a ball of stones, pieces of teeth, shredded flesh from the insides of my mouth and pieces of glass all congealed now, by blood, saliva and with pieces of geel-vet biltong. Much later I was told that the rock had also fractured my skull. I should have known that tyres and boulders stacked across a road were a sign of protest action, but this day my journalist instinct had not kicked in. It was not worth pursuing the story.

Bloody, broken and drifting in and out of consciousness, I kept driving, swerving on and off the road and across the median constantly repeating to myself; “Keep driving. Do not pass out. They will set the car alight with you in it”. “Keep driving. Do not pass out. They will set the car alight with you in it”.

Swerving along the road between the mountains and the ocean I was dead afraid that that would be my fate. I don’t have any memories of the road or the mountains or the sea, only of the chant-like “Keep driving. Do not pass out. They will set the car alight with you in it”. “Keep driving. Do not pass out. They will set the car alight with you in it”.

I reached my village, stopped at the shops, opened the door, and fell out: “Please call an ambulance.” Several women in the village came to help, offered rags and paper towels to stop the bleeding. The owner of the local deli Ellie Wessels brought rolls of paper towels.

The ambulance arrived. By now I was incoherent. They placed my neck in a brace and I was taken to the nearest hospital 40km away where I was tested for the dreaded virus, had my bottom lip stitched up – excruciating pain began to set in – and I was wheeled off to a ward. I was left, necessarily, alone for almost 24 hours until I was declared Covid-free. Later that day, on 6 October, I had maxilofacial surgery to clear my mouth.

Two plates were inserted at the front of my mandible to hold my jaw together. I had no pain, just a general soreness and discomfort, thanks to a lot of chemicals.

Four days after the surgery, from somewhere in Western Asia a cousin, Anwar Lagardien, booked me a taxi online and I returned home to my shuttered container home in Pringle Bay. That was when I collapsed in pain and anger, disappointment and sadness. I was now just one of the very many people who had lost their lives or well- being in South Africa’s swirling spiral of violence. I managed a brief chuckle when I recited (to myself) a short line from a poem by Tony Harrison, A Kumquat for John Keats: “last year full of bile and self-defeat I wanted to believe no life was sweet”.

I tried to hold onto the belief that there was life after misery and despair. There was no such luck. I was living my misery. Within two or three weeks of the first two surgeries on my jaw and mouth a slight soreness I had had for several months as a result of the sedentary life forced upon us by the Covid-19 lockdown – where every day I went from bed to desk, to dinner table, back to desk and then bed again – became terribly painful and was diagnosed with a “sciatica problem”. At first my left buttock hurt. Then the pain became diabolical. The pain in my left buttock that now radiated down my left leg became worse. I woke up one morning in early January and I had lost all life in my left leg. I crawled to the bathroom.

Too white to be coloured, too coloured to be black is published by Melinda Ferguson Books, which is an imprint of NB Publishers and retails at R290

About the author

In the late 1980s Lagardien worked as a reporter and photojournalist for the Weekly Mail and Sowetan. He studied at the London School of Economics and received a doctorate at the University of Wales. Today he's a leading political economist, and writes for Business Day, the Daily Maverick and VryeWeekblad.